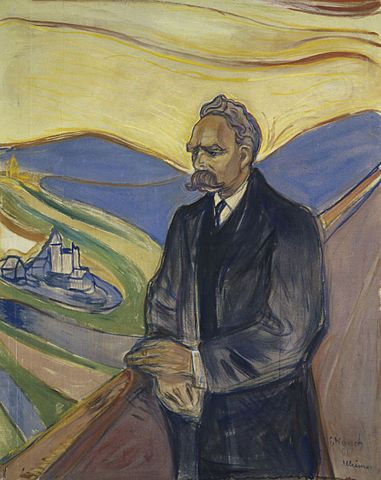

His work has influenced diverse groups including Marxists, Anarchists, and Conservatives. Freud, Heidegger, Jung, Hesse, Camus, Sartre, and Kafka have been influenced by his work in one form or another.

So who was Fredrich Nietzsche? Born in Germany in 1844, he was above all a keen observer of the human condition. Before making his mark on the world as a philosopher, he was a professor of philology at Basel University, a post he obtained at the young age of 24. It wouldn’t be until his 30s that he would strike it out on his own after having already published The Birth of Tragedy and Human, All Too Human.

It was during this period of independence that he would go on to write his most influential books including Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Beyond Good and Evil, On The Genealogy of Morals, and The Antichrist. His ideas were provocative and controversial. They shocked the world, particularly3 his critique of Christian morality and the Enlightenment ideas that underpinned Western philosophy.

In this post, we’ll stay away from his more controversial ideas, and instead, focus on three ideas that are relatable to readers today. They include self-overcoming, the eternal recurrence, and suffering as a catalyst for greatness.

1. Self-overcoming

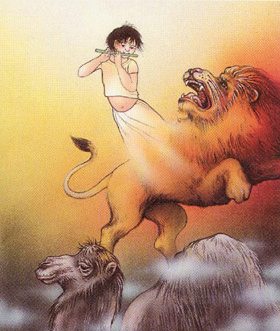

Nietzsche thought of as the great systems destroyer. He believed from birth that we are burdened with ideas and scripts which seek to confine our ability to self-actualize. In fact, the highest act of self-reflection in Nietzsche’s opinion was the revaluation of all values. This meant reconsidering your thoughts on good vs. evil, what constitutes a good life, and other foundational concepts that have been conditioned into you from a young age. To that extent, he offers the following analogy as a method for metamorphosis and coming into your own.

Life has us start as camels, burdened with cultural baggage. These are things passed down throughout generations without question. For example, the idea that subverting authority is bad, and that being docile and meek is good.

To evolve beyond the camel, one must become a lion. This entails embracing nonconformity, conquering your will and creating freedom for yourself. It’s about saying “No” and shaking off excess baggage.

At a certain point, however, you need to evolve once again into the child, which represents innocence, forgetting and a new beginning. The child embodies the sacred yes. An entity that is capable of saying yes without reservation, even to suffering. This final stage of metamorphosis naturally leads to Nietzsche’s next idea of life-affirmation and the eternal recurrence.

2. Life-Affirmation and Eternal Recurrence

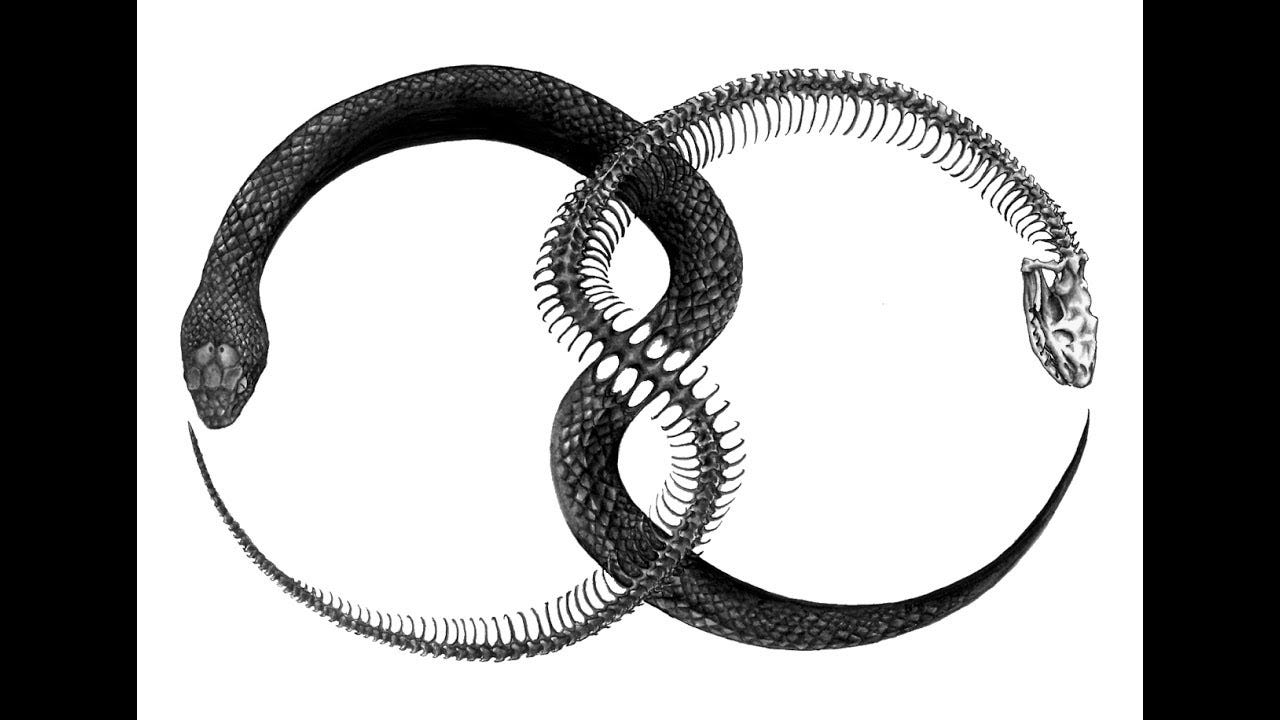

In “The Gay Science”, one of Nietzsche’s more personal works, he offers the following thought experiment:

“What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: ‘This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unutterably small or great in your life will have to return to you, all in the same succession and sequence — even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned upside down again and again, and you with it, speck of dust!’”

For Nietzsche this thought experiment represented the absolute necessity of Amor Fati, learning to love and say yes to your fate. Not wanting anything to be different, not backward, not forwards, for all of eternity.

He furthers his point by saying “Did you ever say yes to a pleasure? oh my friends, then you also said yes to all the pain. All things are linked, entwined, in love with one another.”.

This capacity to say yes, even to the difficulties is one that is obviously not easy. It’s much easier to deny, numb, forget, and distract yourself from that which is most painful.

There are whole industries built which seek to profit from one’s inability to say yes to suffering. Yet it is the exact act of saying yes to suffering, that leads one into our next idea which is the notion that suffering is a natural catalyst to greatness.

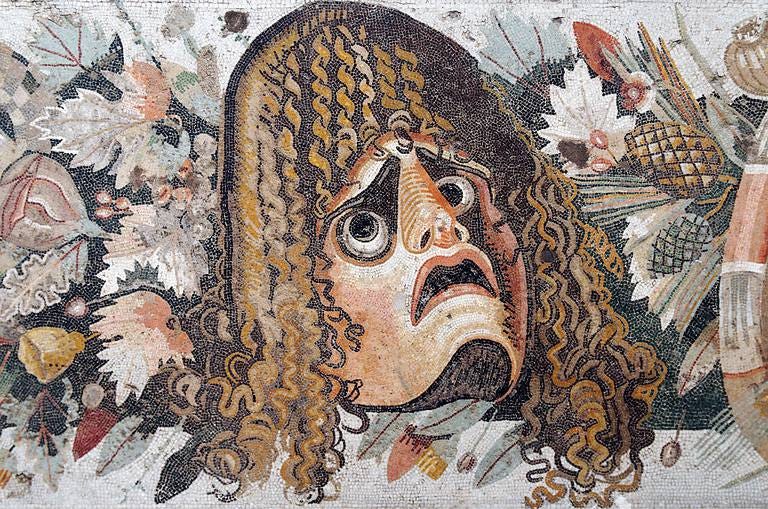

3. Suffering as a catalyst to greatness

If you asked Nietzsche what he wished for his close ones, he would’ve responded with the following:

“To those human beings who are of any concern to me I wish suffering, desolation, sickness, ill-treatment, indignities — I wish that they should not remain unfamiliar with profound self-contempt, the torture of self-mistrust, the wretchedness of the vanquished: I have no pity for them, because I wish them the only thing that can prove today whether one is worth anything or not — that one endures.”

Now on the surface, it seems cruel to want to wish these things on those you hold dearest. Rather good health and happiness seem like the more appropriate thing to wish for. However, for Nietzsche, happiness was not an end in itself. To truly experience the beauty of life, one needed to suffer. In his mind the deeper the descent, the higher the exaltation.

Yet this passage is also powerful in that everybody will inevitably suffer. There is no escaping this part of life. Sooner or later, you will suffer tragedies, and the best response in those situations is to turn your affliction into an advantage.

Rather than let these moments wreak havoc, let them act as teachers. The most spiritual human beings are often those who experience painful tragedies. These painful moments serve as a catalyst to break the shell of their previous self and allow a beautiful transformation to occur. After all, how could you become new without first becoming ashes?

The particularly nuanced point he made was that merely eliminating pain would be deemed goodness, however putting pain to work is a necessary prerequisite to greatness. Rather than dull and push away your suffering, the alternative is to transform agony and suffering into beauty and art. For generations, artists and creators of all kinds have used their pain as life fuel to create beautiful works of art and told stories that resonate with the core of what it means to be human. There is a sense that to be great, one must learn to heroically endure their suffering.

As a final note, Nietzsche knew that not all of his ideas would resonate with everyone. Instead, he writes for those individuals capable of being a value-creators and who can break out of the herd mentality. In his book Zarathustra, he uses the main character as a mouthpiece to explore several of his more intriguing ideas, and leaves the reader to ponder the following question:

“I am a law only for mine own, I am not a law for all. This is now my way, where is yours?” — Zarathustra