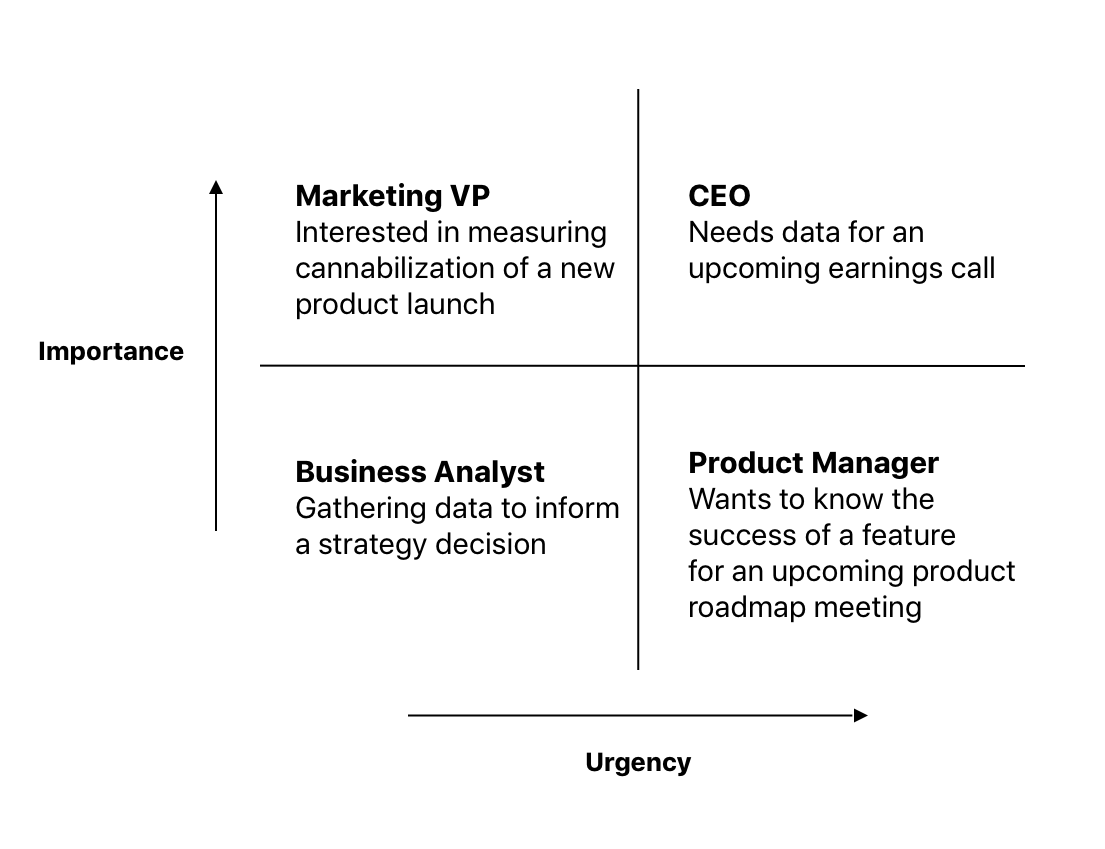

Data scientists must constantly deal with the tension between short-term requests and long-term projects. Neglect the long-term projects, and you risk having minimal impact. However, neglect the short-term requests, and you may find yourself out of a job.

As a result, the best data scientists are those that can split their time effectively between short-term requests and long-term projects. In practice, this can be quite difficult because there is never a shortage of questions that your stakeholders may ask. Some of these questions are urgent and important, while others are neither important nor urgent.

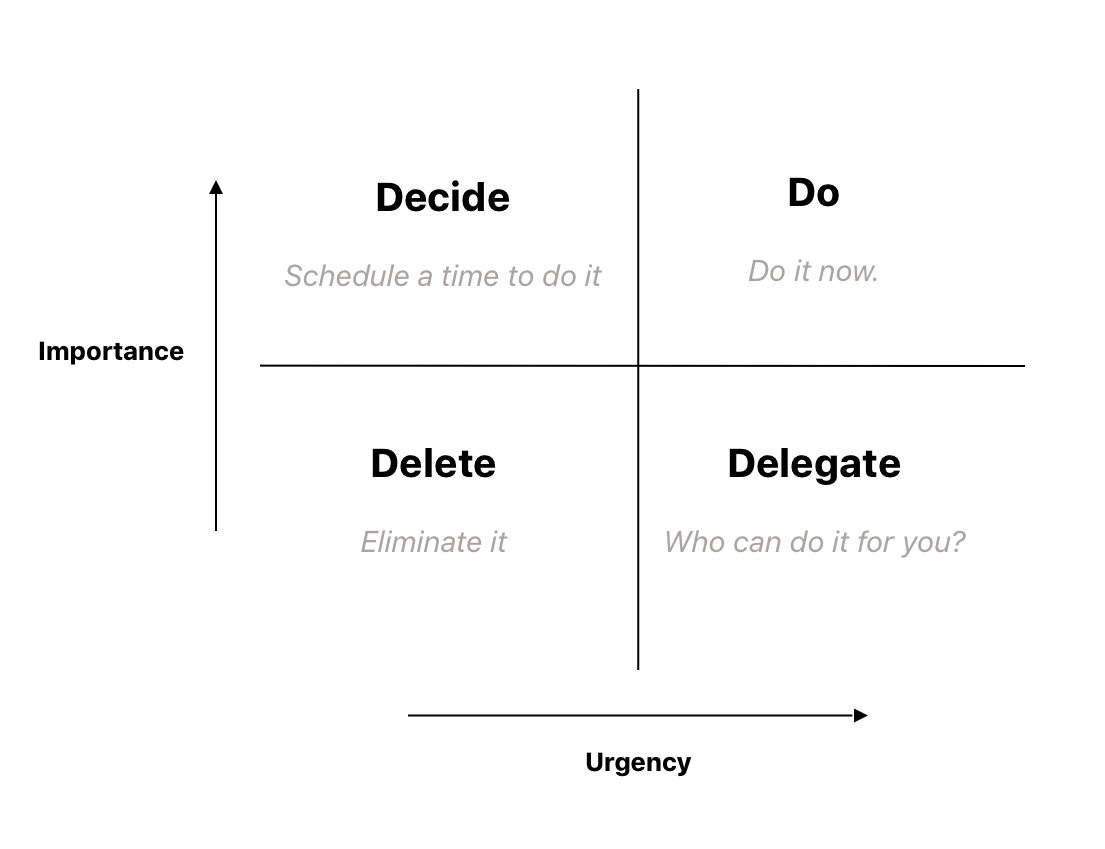

Dwight Eisenhower, a former US President, coined the idea of using urgency and importance to help him prioritize his tasks. Using the Eisenhower Matrix, he was able to ruthlessly prioritize his day.

In this article, we’ll explore this idea, and how it can help data scientists deal specifically with stakeholder requests. We’ll go through effective strategies to deal with each of the four quadrants below.

- High Importance / High Urgency

Typically when you get these requests, everything else gets dropped. There isn’t much leeway here, except for anticipating and planning for these types of requests.

For example, if you know that at the end of each quarter you’re responsible for pulling data and commentary on business performance, you may find it helpful to automate some of that work. Spotting repeatable work that is automatable, especially with high importance and high urgency tasks, will help you establish credibility as someone who can accomplish objectives quickly.

2. High Importance / Low Urgency

When it comes to high importance and low urgency requests, you may find yourself wanting to dive right in. However, the more prudent approach is to first understand what is being asked of you.

Often you can negotiate these types of asks and whittle them down to something more manageable. For example, a marketing executive may send a laundry list of data pulls they need to understand the effects of cannibalization. The reality may be that only one or two of the data pulls are necessary to tell the story they want to tell.

In general, with high importance and low urgency requests, you should strive to create a dynamic of strategic adviser, rather than that of an order taker. Having a unique point of view and leaving your stamp on the project will ensure a seat at the table for any future projects.

Since this is a low urgency request, you should use your best judgment whether you should re-prioritize your current queue of work (including that of long-term projects). Sometimes despite the importance of the problem, you may find it better to push back and set a future date for delivery.

3. Low Importance / High Urgency

Just because something is urgent, does not make it important.

If someone needs data by a certain date, you shouldn’t drop everything you’re working on to meet their deadline. Particularly if the request is of low importance (stack ranked against other requests and long-term objectives you’re working towards).

The best way to deal with these requests is to get more information. Sometimes all it takes is a 15-minute phone call to realize that the extra work required to pull the data, may end up just being an appendix slide that never gets brought up in the meeting. In this case, you can defer to the time when the data is actually necessary.

In cases like these, you could explore a rotation model, where each member of your team is “On-call” for these types of requests.

4. Low Importance / Low Urgency

The final, and trickiest quadrant are those requests that are of low importance and urgency. In the Eisenhower model, we would simply “Eliminate” these tasks. In a company setting, you have to be a bit more delicate with how you respond to these types of requests.

One easy way to defer these kinds of tasks is to put the onus on the stakeholder to do some work first. It might be a few pointed questions that require them to do some leg work before you start pulling any data. This will either buy you time, or they may lose motivation if the request wasn’t that important in the first place.

You can also try to delay the delivery of the work, communicating your current list of priorities and letting the stakeholder know that they should follow up with you in another week or two once things have settled down. The key is to never outright say no, but rather communicate your list of priorities to help the stakeholder understand the difficulty you may have with answering their questions at this time.

Long-term these kinds of asks may surface the need to create self-service options. A good rule of thumb is that anytime you get asked three different times to either update analysis, or pull data to answer a similar question, you should explore a dashboarding or automated solution.

So next time you have a request sitting in your email, consider which of the four quadrants it would fall under. After doing so, you can then take the corresponding measures. You’ll inevitably make some mistakes, but the alternative of trying to keep all your stakeholders happy by simply being an order taker will diminish the impact that you can have as a data scientist.