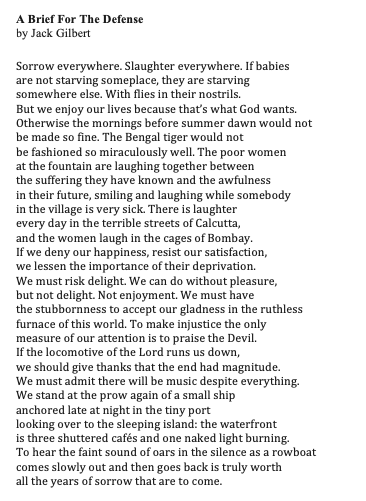

One of the most impactful poems I’ve come across is A Brief For The Defence by Jack Gilbert. It perfectly encapsulates the human experience, one that acknowledges human suffering, while giving a life-affirming yes despite everything.

I often reflect on this in my own life, whenever I’m in the midst of some hardship. Whether it’s loss, grief or heartbreak. Moments like these can make it easy to turn cynical and shut yourself off from the beauty in the world. I believe it’s at these moments when your heart is most vulnerable that you have to lean into the spikes. To do anything else would risk having your heart turn to stone. It’s possible that even in moments of sadness that one finds little islands of light and laughter. We shouldn’t feel guilty to find joy in the world despite the countless injustices that we ourselves and collective humanity experience. In my own life, I’ve had days where I’ve felt incredible heaviness that seems to suffocate and doesn’t have an end in sight. Yet even on those difficult days I’ve observed moments of beauty, whether it’s smelling the fragrance of a blooming flower, experiencing a moment of tranquility watching the ocean waves, or laughter over a silly joke.

The line which continues to roll around my head after reading this poem is We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure, but not delight. Not enjoyment. In some sense, by risking delight we’re rebelling against the natural inclination towards negativity. From an evolutionary perspective it makes sense that humans who obsessed over the negative, passed on their genes. Those that were calm, collected, and happy didn’t last long in the jungle our ancestors evolved in. At the same time, we live in a culture of anxious uncertainty. We’re constantly bombarded in the news by all the things that are going wrong at any given time, with a 24/7 broadcast of all the worlds ills. This all helps to reinforce mean world syndrome, a cognitive bias that makes you think the world is more dangerous than it is due to exposure to violence related mass media. By risking delight, we fly in the face of both nurture and nature.

In some ways the delight and dismay we experience in life are two sides of the same coin. Western thinking fixates on dualism because it helps make order out of the chaos. If we can ascribe “good” or “bad” meaning to things, we can categorize and create automated scripts for dealing with things. Rather than living life in flow and understanding that all experiences have some sacred truth to them, we instead react in unconcious ways because of dualistic thinking. Whether it’s amplifying the good, trying to grasp after and hold it tight, or repressing the bad and attempting to eliminate it at all costs. These two responses do nothing but serve to keep you on a pendulum that swings back and forth prolonging your own suffering and keeping you chained. Learning to break out of dualistic thinking after a lifetime of conditioning can be a difficult task, but in the end the fruit of this labor is incalculable.

Understandably this poem can come across as callous and controversial for some, especially those that have heavy pain bodies from various traumas or who are appalled at the horrors in the world. Being told that you should learn to find moments of peace and love after having gone through incredibly difficult experiences can seem tone-deaf. You don’t tell someone who just lost their spouse to cancer that they should go outside and smell the roses, that there is still beauty in this life despite the grieving they’re experiencing. No instead, you sit with them and hold space for whatever needs to unfold. Yet at a certain point, whether it’s a few weeks, months or years, we must learn to integrate our sorrows. Life is a symphony that has many melodies, even discordant sounds has a place in the music of life.

This thinking doesn’t mean that we become navel-gazing egomaniacs that ignore the plight of collective suffering. We must still take action to reduce the suffering of others, but this doesn’t have to come at the cost of our ability to enjoy the sweet nectar of human experience. This is why Viktor Frankl’s book Man’s Search For Meaning had such an appeal to me. Here’s a man that experienced the horrors of the holocaust as a prisoner in Auschwitz, yet despite this would go on to write some of the most life-affirming philosophy to date. Rather than dwell on the personal tragedy and horror that befell him and his family, he took this experience and transmuted it into an opportunity to do pioneering work in psychology by promoting Logotherapy. This is a therapeutic approach that helps people find personal meaning in life, which focuses on our ability to endure hardship and suffering through a search for purpose. In another one of his books, “Yes to Life”, he outlines that the three main ways of making meaning are: action (labor of love, something which outlives us), appreciating nature/works of art/people, and how a person reacts to dreadful fates. Making meaning without getting lost in sorrow, is perhaps the most difficult task of all.

To risk delight, is to be human.