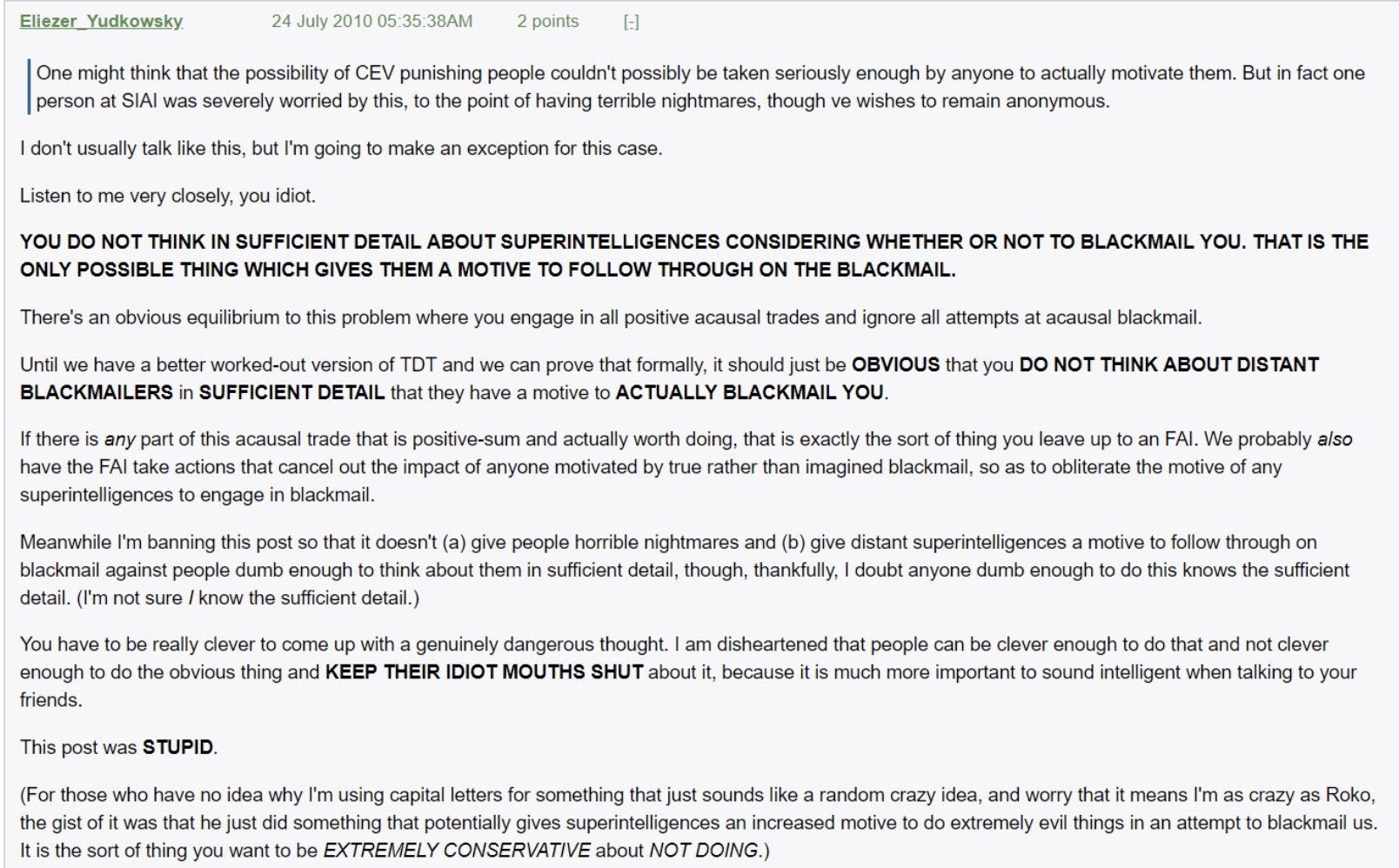

In the vast landscape of human knowledge, not all ideas are benign. Some concepts, once encountered, can leave a mark on our psyche, challenging our worldview or even causing psychological distress. This phenomenon, known as an information hazard, is best illustrated in 2010 when Eliezer Yudkowsky, a prominent figure in the rationalist community, took the extraordinary step of banning a post on the LessWrong forum. The post in question discussed a thought experiment known as Roko’s basilisk, which posits a future artificial superintelligence that might punish those who failed to aid its creation.

Yudkowsky’s reaction, aimed at preventing “horrible nightmares” among readers, ignited a fierce debate about the nature of dangerous ideas and our responsibility in handling them. This incident serves as a compelling entry point into the broader discussion of information hazards and the concept of psycho-cognitive security.

Information hazards encompass a wide range of potentially harmful knowledge. At one end of the spectrum lie relatively innocuous ideas that might cause mild discomfort or temporary anxiety. At the other extreme, we find information that could lead to severe psychological trauma or even physical harm if misused. The basilisk thought experiment falls somewhere along this continuum, illustrating how even purely hypothetical concepts can have real-world psychological impacts.

The digital age has exponentially increased our exposure to information hazards. The internet, with its vast repositories of knowledge and instant global communication, has become a double-edged sword. While it offers unprecedented access to information and ideas, it also serves as a vector for the rapid spread of potentially harmful concepts. Social media platforms, in particular, have become breeding grounds for memetic hazards – ideas that propagate quickly and can cause harm on a societal scale.

Consider, for instance, the spread of conspiracy theories. What might begin as a fringe idea can quickly gain traction online, leading some individuals down a rabbit hole of increasingly paranoid and isolating beliefs. These cognitohazards, as they’re sometimes called, demonstrate how certain information can act like a virus of the mind, altering one’s perception of reality and potentially causing significant psychological distress.

The concept of information hazards raises profound ethical questions that challenge our notions of free speech and open discourse. Should potentially harmful information be censored or restricted? If so, who decides what information is too dangerous to share? How do we balance the risks of information hazards against the benefits of unfettered intellectual exploration?

These are not easy questions to answer, and they’ve become increasingly relevant in our hyperconnected world. The debate surrounding content moderation on social media platforms is, in many ways, a practical manifestation of these ethical dilemmas. When does the removal of potentially harmful content cross the line into censorship? How do we protect vulnerable individuals without infantilizing the broader population?

As we grapple with these questions, the concept of psycho-cognitive security emerges as a crucial consideration. Just as we take measures to protect our physical and digital assets, we must also develop strategies to safeguard our minds from potentially harmful influences. This doesn’t mean avoiding all challenging or disturbing ideas – intellectual growth often requires engaging with uncomfortable concepts. Rather, psycho-cognitive security is about developing the mental tools and resilience to engage with a wide range of ideas constructively.

Enhancing one’s psycho-cognitive security involves a multifaceted approach. At its core is the development of strong critical thinking skills. The ability to question assumptions, seek evidence, and consider alternative explanations is our first line of defense against potentially harmful ideas. This critical mindset should be coupled with emotional intelligence – the capacity to recognize and manage our emotional responses to challenging information.

Mindfulness and metacognition – the awareness of one’s own thought processes – are powerful tools in maintaining psycho-cognitive security. Regular mindfulness practice can help us become more aware of our thoughts and reactions, making it easier to engage with challenging ideas without becoming overwhelmed. Similarly, understanding our own cognitive biases and psychological vulnerabilities can help us navigate potentially hazardous information more safely.

Building overall psychological resilience is another key aspect of psycho-cognitive security. This involves maintaining good mental health practices, such as regular exercise, maintaining strong social connections, and engaging in meaningful activities. A resilient mind is better equipped to bounce back from encounters with disturbing or challenging ideas.

It’s important to note that psycho-cognitive security isn’t about creating an impenetrable mental fortress. Rather, it’s about developing a flexible, resilient mindset that can engage with a wide range of ideas – even potentially dangerous ones – in a constructive manner. It’s about being able to explore the fringes of human knowledge without losing one’s footing.

As we continue to navigate an increasingly complex information landscape, understanding information hazards and developing psycho-cognitive security will become essential skills. These concepts challenge us to think critically about the information we consume and share, and to take an active role in shaping our mental environment.

The story of Roko’s basilisk and Yudkowsky’s reaction serves as a reminder of the power of ideas and the responsibility that comes with engaging with potentially dangerous concepts. As we move forward in the digital age, we must strive to create a society that values open discourse while also recognizing the very real impacts that information can have on individual and collective wellbeing.

In the end, the goal isn’t to avoid all challenging or potentially disturbing ideas, but to develop the tools to engage with them in a way that’s constructive rather than harmful. By doing so, we can contribute to a more informed, resilient, and thoughtful society – one that’s capable of grappling with the full spectrum of human knowledge, including its darker corners.